“COVID-19 Is Real and Painful To Live With”, Survivors Narrate Ordeals

Medical doctors, scientists, medical experts and government officials are still learning about coronavirus as it continues to spread here in Rwanda and ravage nations across the globe. So far, the most disturbing finding is that Covid-19 appears to have lingering effects long after a person has recovered.

Scarring of lungs, shortness of breath, lack of smell, and inflammation of the heart, are just some of the ailments COVID-19 patients struggle with long after the acute illness has passed, available research indicates. Most patients hospitalized with COVID-19 have experienced at least one long lasting symptom, even six months after falling ill.

The first case of the virus in Rwanda was announced on March 14, 2020. The Government soon implemented one of the severest lockdowns seen globally, causing economic paralysis and near meltdown. Despite the economic implications, the lockdowns have been effective at mitigating the spread of the virus. As of January 18, Rwanda had recorded only 10,850 cases with 140 deaths. 7193 of those cases are confirmed recoveries, leaving approximately 3,500 cases active in the country as of writing; although, this past week indicated the virus was going nowhere with a seeming spike in the spread.

The Chronicles has independently tracked down and interviewed recovered COVID-19 patients, a first for local media. It was a difficult task finding COVID survivors who were willing to go public with their stories. Officials at isolation facilities have privately told us their workers are encountering stigma in their communities because of their work. The pressure and negative attitudes have been so difficult to bear, that some workers have contemplated quitting their posts.

The Chronicles‘journalist Germain Nsanzimana contacted 15 people who have recovered from the virus. We wanted them to tell their stories of what it’s like to get COVID, and how people have treated them after recovery. Just 5 people agreed to speak on record. Some have quite an ordeal to narrate. We can also authoritatively report that people below 30 years were more willing to speak about their experiences than older categories. Those who declined often explained that they have children, and don’t want to bring them unwanted attention.

Below are some excerpts from interviews we conducted:

Ange Gabriella, 30, Mbugangari from Gisenyi sector, Rubavu district, Western Province

Gabriella is in the business of selling water to Goma in the neighboring DRC. Goma, despite its location on the shores of freshwater in Lake Kivu, does not have an adequate supply of freshwater and is reliant on Rwandan imports to meet demand. Before the COVID pandemic, informal trade of water-filled jerry cans on bicycles, motorbikes and in cars was a common sight. This flow of people is hard to contact trace, and large crowds at the border made for a dangerous environment for transmission. Now, only large trucks are able to enter Goma, and their drivers and staff must stay in a managed isolation facility upon their return to Rwanda. Once the drivers and staff test negative for the virus, they are allowed to return to their homes.

On June 10, 2020, Gabriella went to the Gisenyi Health Center with symptoms of the coronavirus. At the time, she was staying in a managed isolation facility and had tested negative for the virus on three separate occasions. Prior to her visit, she had a bizarre dry cough, constant headache and was fatigued all the time.

At Gisenyi Health Center, Gabriella says medical staff openly spoke that her symptoms were those of Coronavirus infection. Her samples were taken. 24 hours later, a team wearing full personal protective equipment (PPE) arrived at the facility where Gabriella was staying, and took her to the Gisenyi health center where they put her in an isolated room designated for COVID patients.

“It was the beginning of a horrifying experience,” she says. And adds: “I cannot forget how I was mistreated at Gisenyi Health Center. For two weeks, I was locked in a room with no one to talk to. Medical staff just ignored me like I was not existing. It was traumatic for me. As a result, my health deteriorated so much. I felt so sick.”

She continued: “All throughout, ambulances were bringing more people. It was such a frightening experience.”

Gabriella later was moved to Kanyinya Health Center, in Kigali, which is the national referral for Covid-19 patients in critical condition.

She says: “At Kanyinya, the situation was the complete opposite of Gisenyi Health Center. Actually, a few days after I arrived, my condition improved. Doctors at Kanyinya were always passing by to speak to me. They were really caring. It was as if they were family. We could also speak freely with other patients.”

Gabriella spent 28 days at Kanyinya. When she returned home, she locked herself in her house for the first week – avoiding to speak to neighbors and family because of the feeling she could be stigmatized.

She narrates: “I always felt like I had committed an abominable crime to have contracted Coronavirus. But as time progressed, I began coming to terms with the situation and accepting it as any other illness. I’m also glad, in that as I isolated myself, people actually were eager to see me. They were curious and asked a lot of questions about the disease, which I was also happy to explain.”

For Gabriella to accept The Chronicles interview, many intermediaries encouraged her to do so. We are glad she spoke with us.

As to how Gabriella contracted the virus, like all people who get the disease, she cannot pinpoint the exact circumstances. However, she suspects it may have been from one of the truck drivers she encountered on her journeys to Goma.

“Today, I’m very careful with my surroundings. I do my best to ensure I follow the regulations in place like social distancing and constant hand washing. But still, it is God who protects a person from COVID-19. Can you imagine I and other people usually spent days in Congo and didn’t have the virus.”

“But when I look back at how I used to think the government and all those talking about COVID-19 were just exaggerating, I feel bad. COVID-19 is real and painful to live with.”

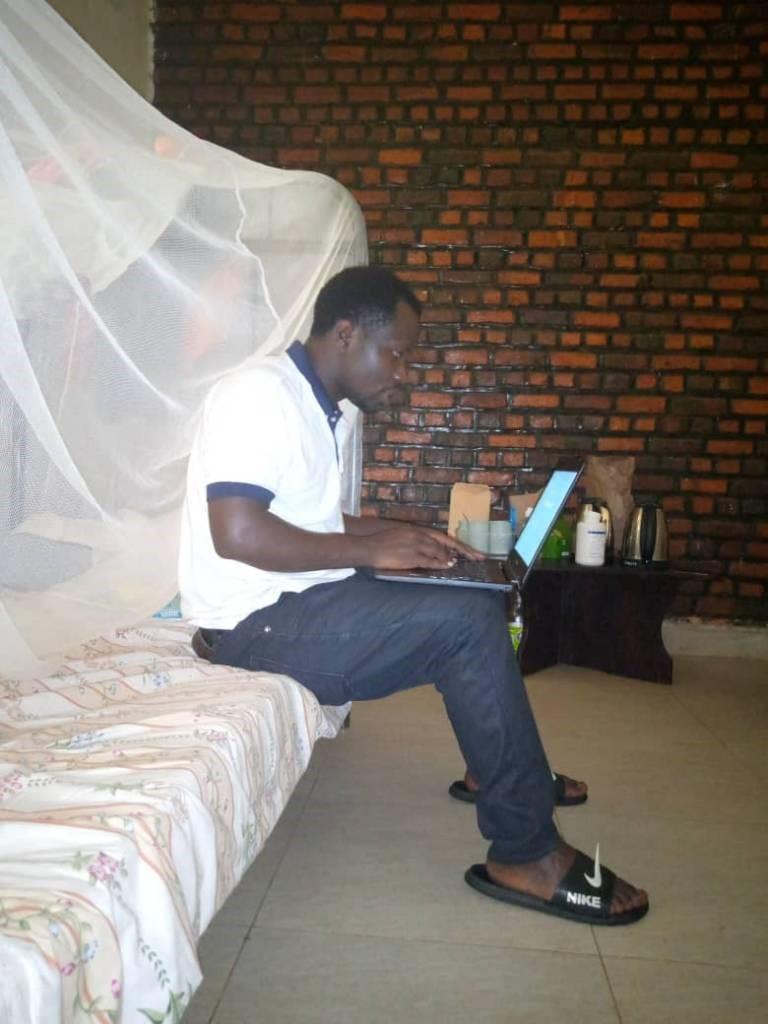

Turahayo Alfred, 22, Nyarwahi village, Nyarurama cell, Ntongwe sector, Ruhango district, Southern Province

Turahayo is a first year student doing mathematics and chemistry at the University of Rwanda (UR) College of Education, also called Rukara Campus. It is located in the Eastern Province.

On December 18, last year, Turahaye tested positive for COVID. Several days prior to his diagnosis, he felt feverish, had a headache and was feeling tired all the time. Turahaye checked in at the campus clinic when he first started feeling sick. He was not advised to be tested, he was only prescribed with pills for fever.

On December 14, his university friend tested positive. Turahaye was traced and called in the same day. Samples were taken and that marked the beginning of his experience with COVID-19. He was treated by Gahini Hospital health officials, but was required to stay in mandatory self-isolation in his university room.

He told us; “For sure I cannot say exactly where we got the virus. If you have been to a university environment, then you know how students act rebelliously about anything they are told. We didn’t take the messages of face masks or sanitizers seriously. We hugged and knocked heads as usual.”

All schools were closed in March 2020. Universities were only allowed to open in September. Turahaye, like all the other thousands of students, were back to their pre-coronavirus ways.

During his isolation, Turahaye was given a variety of treatments, but remembers one which made him fall asleep for hours and hours whenever he took it.

After he was declared COVID-free, he was allowed to mingle back with other students, but no one wanted to be in his presence.

He said: “Whenever I arrived at any place, other students ran away and my friends avoided me. They were scared, saying the virus never leaves the person who has had it. They feared I would infect them.”

What would you do differently if the clock was taken back to when you didn’t have the virus? – we asked Turahaye. “At that time, many of us believed they were just playing us and exaggerating the whole thing. There had been information circulating that the virus doesn’t infect people under 18 years.”

He added: “The lonely time I spent in my isolation room was quite traumatic for me. I wouldn’t wish anyone to live through such a period. Today, you can think there is a new version of me. This habit of hugging or handshaking is history for me. As long as the virus is still around, I will only ever hug my mum. Washing my hands just instinctively happens; I don’t even have to think about it. I do not loiter around like I used to.”

Manzi (REAL NAME WITHHELD), 45, Rubavu district

Unlike the ten recovered COVID-19 patients who refused to say anything when contacted, Manzi did agree, though he didn’t want to say much nor his real name revealed.

He told us before the pandemic, he was engaged in cross-border trade between Rubavu and Goma. Some months ago, the government relaxed the border closure allowing a strictly controlled flow of traders to either side.

Manzi says he was contacted by officials for testing and was found with the virus. Since he was asymptomatic, Manzi was allowed to self-isolate at home. He says he was uncomfortable putting his identity in the media, instead promising to find another person who was infected for us to talk to – which he eventually didn’t do.

After two weeks, and two separate tests, Manzi was told he was virus-free.

He says: “I didn’t take any tablets or any form of treatment. After two tests during the two weeks of my isolation, I was told I had been cured. That is all I can say.”

Clarisse Umutoniwase, 25, Kanyina cell, Gasabo district, Kigali

On August 17, last year, the government ordered closure of two large markets in Kigali, including the ‘Kwa Mutangana’ multi-storeyed market in central Kigali. Markets countrywide had been allowed to operate earlier in May after two months of a biting national lockdown.

The markets were to operate at 50% capacity, with strict social distancing between the stalls. When the ‘Kwa Mutangana’ market was ordered shut, the health ministry said many COVID-19 cases had been identified. Everyone working from the facility was required to be tested.

It is from this mass testing that Umutoniwase was found to have the virus. She was selling fruits from the market.

After a week waiting for results, Umutoniwase received a call from medical officials who required her not to move as she had the virus. She was transferred to Kinihira Hospital, a major facility located in rural Rulindo district in Northern Rwanda.

“I was very surprised when they told me I had the virus,” she says. “My health was perfect with no single sickness. I had no symptoms whatsoever.”

There, Umutoniwase would spend 18 days in the COVID-19 section along with many other patients.

She narrates: “The region where Kinihira Hospital is located was very cold and that affected me. I developed tonsillitis for which I was given some pills. I don’t like tablets so I took just one and was fine soon after.”

“While I was healthy, it was kind of emotionally draining to see others who were in visible pain. There was this woman who would spend the day OK, but then became seriously ill at night. I was scared that at some point I would also be in the same condition.”

She continued; “During some of the days, my throat was hurting and it was the first time I had ever felt like that. Doctors said my case was not complicated because I had tested positive at the stages of the virus.”

“Kinihira medical staff encouraged us to engage in exercises like jogging. So every morning, I would run around and other exercises with other colleagues. Following each session, it felt really refreshing.”

Umutoniwase was tested three times while at Kinihira Hospital, which all turned out positive. “It was shocking for me every time the results came back. Apart from the brief tonsillitis and pain in my throat, I didn’t feel sick,” she said.

After eventually testing negative, Umutoniwase was discharged. She continued with physical exercises.

As to life after the COVID-19 bout, she says: “My family was very happy to see me back in as good health as I had left. They told me they were very worried since people were dying in big numbers elsewhere. I have continued with physical exercises, drink ginger tea whenever I can, and I’m also very careful with how I relate with people. I do not joke with the government’s pleas for us to maintain social distance and wear masks.”

Today, Umutoniwase no longer operates a fruit stall in the market. She works as an agent for IREMBO, the government’s services online portal.

Zachee Ntakirutimana, 27, Rebero village, Mpinga cell, Gikundamvura sector, Rusizi district

Ntakirutimana is a student at the University of Rwanda, Nyagatare Campus, located in Eastern Province, where he is also a Guild Minister for Planning and Production. Towards the end of December 2020, Ntakirutimana’s roommate developed a very high fever. They checked him in at the campus clinic where tests found no illness.

He told us; “We were immediately referred to Nyagatare Hospital, as the university clinic suspected it was COVID-19. The results came back on December 31, and he was positive. I was required to take the test the next day. It was positive too.”

Surprisingly, Ntakirutimana says he decided to share his results on WhatsApp groups where he was a member. “As a student leader, I felt it my duty to sensitise other students and anyone I could reach to follow regulations to the letter because the virus was real,” he said.

Ntakirutimana tells us that a day after testing positive, his condition changed. He was vomiting repeatedly, had high fever, coughing and had a pounding headache. The treatment involved different medication to treat those symptoms, and was encouraged to do regular physical exercises to keep the lungs healthy.

Once discharged, Ntakirutimana says he was received with curiosity by some students, as they asked many questions about the virus. Some students, he said, also avoided him at first, but would later change.

When The Chronicles interviewed Ntakirutimana, he was back home in Rusizi, where he says is concerned at how disinterested local residents are about the virus.

Rusizi, like Rubavu district, was also maintained in special lockdown for weeks due to unusually high infection rates in the two districts, both bordering DR Congo.

Ntakirutimana said of the situation in his area: “When I tell people I had COVID-19, they are surprised. Some get interested to know more. In some cases, the moment people around found out I had had the virus, they took some distance away. They tell me that they don’t think the virus is completely out of my body.”

The Bottom Line

Although we were only able to interview 5 people, there are some clear similarities. These people were contact traced and tested by the government, and then moved to isolation facilities or told to self-isolate. Government systems are working well to identify cases, and patients are receiving adequate care, although some have experienced mental problems and conflicts with staff in isolation. After recovery, there is a common theme as well: an inquisitive community is skeptical at first of recovered patients, but learns there is little to fear, but they must adhere to the rules.

As is clear, recovered patients are advocating for mask wearing, social distancing and washing hands as healthy professionals’ advice. They take the virus seriously and encourage those around them to do so as well.

Covid is real. Follow the science, protect yourself and community.