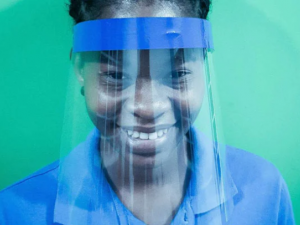

Ugandans melt plastic waste into coronavirus face shields

When the Ugandan government ordered all non-essential workplaces shut to contain the coronavirus pandemic in late March, Peter Okwoko and his colleague Paige Balcom kept working.

But the pair - who had been turning collected plastic waste into building materials such as roofing tiles and pavers since last year - shifted gear and instead began manufacturing makeshift plastic face shields from discarded plastic bottles.

When they posted pictures of their prototypes on social media, they got a surprise phone call from the local public hospital.

“The doctor from Gulu regional referral hospital requested we make 10 face shield masks urgently because they didn’t have enough” and the hospital had just received its first Covid-19 patient, said Okwoko, 29, a co-founder of Takataka Plastics.

The social enterprise set to work shredding plastic, melting it and shaping the liquid plastic into face shields and frames, using locally made moulds. Soon a first set of shields was delivered.

But “in the afternoon, the hospital called again. They said they needed more face shields because the previous ones had worked out well for them”, Okwoko said.

LOCAL PROTECTION

As the coronavirus pandemic continues to burn around the world, it has also caused severe disruptions in supplies of personal protective equipment (PPE), according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

The problem is particularly severe in poorer countries with few resources to pay high prices in a competitive global market. In March, WHO officials urged companies around the world to increase production by 40 percent if possible to meet growing demand.

In Uganda, medical workers have discussed work boycotts to protest the lack of protective equipment in hospitals, especially after several healthcare workers were confirmed infected with the virus.

“The situation is critical. Many people are working without PPE,” Dr. Mukuzi Muhereza, secretary general for the country’s health workers’ body, the Uganda Medical Association, warned last week.

“That is hampering the fight against Covid-19 because there’s fear among health workers that anytime I touch a patient I might be a Covid patient myself,” he said.

Late last month, the Ministry of Health said Uganda’s public hospitals are likely to run out of existing stocks of protective equipment within three months.

“It’s true we are facing shortages in PPEs,” Emmanuel Ainebyoona, a spokesman for the ministry, told the Thomson Reuters Foundation in a phone interview.

“We are urging all hospitals to utilise the little they have by prioritising (medical workers) who are at most risk.”

In his state of the nation address last week, President Yoweri Museveni said the East African nation - which so far has about 650 confirmed cases of the virus - has certified 10 local industries to begin making PPE.

But Takataka Plastics has been manufacturing in Gulu since March, with 14 staff now having made about 1,200 of the recycled plastic face shields, Okwoko said.

About 500 have been sold at low cost to NGOs and private health facilities and an additional 700 donated to public hospitals, he said.

Balcom, 26, a mechanical engineer who met Okwoko in 2019 while doing research on plastic pollution in Uganda, said some of the material used in the face shields now comes from hospital waste, such as used intravenous drip bottles.

Six of those making the shields are homeless youths employed by the group, she said.

MELT, POUR, PROTECT

To make the face shields - a two-day process - workers sort, clean, shred, melt and mould the waste plastic. Then they attach an adjustable strap, sometimes made from slices of old bicycle inner tubes.

The group is manufacturing both single-use shields that cost about one dollar (3,000 Ugandan shillings), with frames made of cheap foam, or reusable ones, with plastic frames, that cost about $2.70 (10,000 shillings), Okwoko noted.

In a country where an estimated 600 tonnes of waste plastic is thrown away daily - more than half it uncollected and less than 5 percent recycled - the effort is also helping battle plastic pollution and dirty air.

Burning of plastic waste - which can produce toxic gases and carcinogens - is common, Balcom said.

In the northern town of Gulu, where Takataka operates, at least 80 percent of plastic waste isn’t collected, she said, and piles of it end up in waterways, on roadsides and on vacant land.

Takataka now hopes to expand its operations into a full-scale plastic processing plant capable of recycling 9 tonnes of plastic waste monthly, up from about 60kg of plastic a day currently.

But “our focus at the moment is to fight Covid-19,” Balcom said.